by Saskia Kowalchuk

“You aint f*** with me way back when, but how ‘bout now? Now I’m a YouTube compilation”

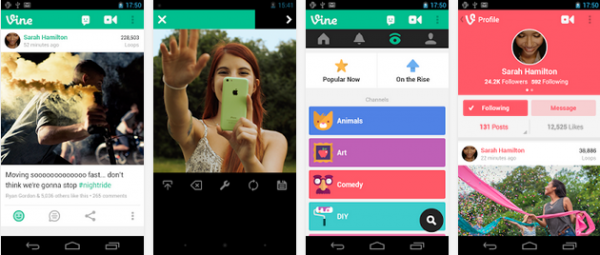

How come, in 2020, “RIP Vine” is much more salient sentiment than “do it for the Vine” was in 2015? Vine is a now-defunct app for creating and sharing 6 second looping videos. Launched in 2013 and active until 2017, Vine was purchased by Twitter from its creators in 2012 for 30 million dollars. This was a time before Periscrope, Facebook Live, IGTV, or Twitch.tv, meaning that video sharing landscape was dominated by YouTube. Vine seemed like a natural fit for Twitter ownership. The short format of the videos echoed the 140-character limit for tweets, and spurred a new form of entertainment. However, the difficulties in governance experienced by the platform, which included such common struggles as monetization and content moderation (Gillespie, 2017), dictated that Vine’s reign would be short-lived.

What remains most notable about Vine is its technical affordances. From a connectivity standpoint, Vine’s technical affordances largely mimicked those of Twitter. Hashtags were hyperlinked and searchable; popular content was prioritized on the explore page; users’ likes were transparent and visible on their profiles; and “revining” allowed users to share the vines of other users on their own feeds. These considerations allowed content to reach viral heights, which have had lasting impacts on both meme culture and Internet culture more broadly. Moreover, the same linguistic cues were employed on both platforms: the unique content outputs referring to the platform name (tweet, vine), which necessitates terms such as “retweet” or “revining”, as opposed to merely “sharing”. Indeed, this epitomizes both Gillespie and Van Dijck’s understanding of a platform as “a mediator rather than an intermediary: it shapes the performance of social acts instead of merely facilitating them” (2013, p. 29). In this view, View was always destined to reap the rewards of Twitter’s model but would also face similar shortcomings.

From a creative standpoint, the six second video that looped continuously encouraged content that benefitted from multiple replays or could be played seamlessly through looping. Video could be shot through the in-app player which would record only when a finger was held down on the screen, or could be shot on a phone, uploaded from a user’s camera roll, and edited down to the appropriate length. These affordances helped to form a new “technological unconscious” (Van Dijck, 2013, p. 32) upon which a new cultural formation could cohere. Furthermore, users could upload audio tracks overtop of the video, which included commercial hits, and spurring memetic musical motifs, such as Enya’s “Only Time”, without fear of legal reprisals. Given the remix style and short form of the videos, creators could rest assured that their content adhered to the tenants of fair use law. Specifically, the six-second length was at the heart of this affordance since it adhered to a legal precedent related to sampling in the music industry, established in the 1990’s (Roberts, 2013). Interestingly this did not prevent Prince from filing an uncontested takedown request for 8 instances of fans posting concert footage to the platform (Blistein, 2013).

Technical affordances not only produced novel forms of video content, but also gave way to a new form of celebrity. These were individuals with high energy and a sense of humor that was legible in six second chunks. This included individuals such as Victor Pope Jr., Lele Pons, Gabbi Hanna, and King Bach. These young creators quickly learned how to maximize engagement by optimizing posting times and strategically incoperating trends; information that they shared with one another through group chats (Lorenz, 2016). Viners formed friendships and began producing collaboration videos to share social capital and grow their audience. This cooperative mindset is epitomized by the phenomenon of 1600 Vine Street: a Los Angeles apartment complex where many Viners resided in the early days of their full-time Vine careers. This locality allowed them to film together frequently, and physically establish the Vine community in material space. Indeed, this display of user agency affirms the precarious position that influential users occupy, as they are located somewhere between amateur and professional in an emerging channel with shifting norms and expectations (Van Dijck, 2013).

What proved to be Vine’s downfall, beyond a terminal decision from Twitter, was the corporate administration’s unwillingness listen to creators about how to continue to grow the platform. Most prominently, many creators faced issues with abusive and harassing comments, which Twitter was slow to resolve (Lorenz, 2016). This has repeatedly proven to be one of the prime questions of platform governance when contending with Twitter (Gillespie, 2017; Van Dijck, 2013), so it is unsurprising that the issue arose on Vine. Indeed, Twitter has proven a major proponent of the view of platforms as neutral conduits who bear minimal responsibility for the potentially harmful content hosted on their servers (Gillespie, 2017). This emancipation of duties to protect both prominent and quotidian users from harassment is dangerous and harmful to profitability.

Technical affordances proved limiting as well, as creator requested an improved recommendation page and a more functional suite of editing tools. Many creators pointed to the YouTube approach of directly supporting creators through financial compensation or use of creative space as a necessary investment in growth. When Vine did not deliver on these considerations, top creators shifted energy away from Vine and engagement plummeted (Lorenz, 2016). This disregard for the concerns of the top users driving views on the platform was the kiss of death for app, which announced its impeding termination of services in October 2016. Remarkably, following Vine, many top creators have rocketed to fame on others platforms. Some, such as David Dobrik, Jake and Logan Paul, and Kody Ko, have sought major success on YouTube. While others, such as Shawn Mendes or Liza Koshy, have levied their Vine fame into a launch pad for traditional media careers. Ultimately, Vine’s inability to recognize the value of its prominent users’ following, as they were so-called influencers in a time before influencers consolidated their dominance in the online marketing sphere, proves shortsighted.

Lastly, it is necessary to examine Vine within the larger trajectory of video sharing platforms, including YouTube and TikTok. Since Vine’s untimely demise, not only have Vine stars migrated to YouTube to continue their careers as content creators; but many of the beloved videos that defined the Vine era have been immortalized in compilations bearing ironic titles such as “Vines That Keep Me from Ending It All.” Though the looping feature is not accessible in the same way as on Vine, users can replay the video repeatedly or the uploader can string the clip together repeatedly to mimic the original looping effect. This process of user driven archivism is necessary act of preservation since the skeleton of the Vine site does not allow for browsing, and only provides access to videos if the user has the direct link to the original post. This is compounded by the fact that during the run up to the site’s closure in January 2017, creators were offered the opportunity to download their videos and deactivate their profiles, rendering any record of their time on the site null. This quandary is itself a fascinating articulation of the issues surrounding content ownership, and readily demonstrates the tension between platforms as techno-cultural constructs and as socioeconomic structures (Van Dijck, 2013).

As opposed to a preservation of Vine’s status quo, Tik Tok offers an ambitious expansion of its techno-cultural construct (Van Dijck, 2013). Developed by Chinese-owned ByteDance, which purchased lip-synching app Music.ly in 2017, Tik Tok is proving to be a potent meme-making enclave. Its technical affordances, which includes a robust suite of editing tools; text appliqués for videos; and duet mode which embeds one Tik Tok within another, are quite spectacular. Formally, Tik Tok represents extension of Vine in its prolonged time limits for videos. Initially 15 seconds and now upped to 60 seconds, Tik Tok creators can experiment with content that builds more flexibility into its temporal structure. These creative tools are further empowered by a precise and forceful algorithm for suggesting new content. Ultimately, these tools were largely what the alienated Viners demanded from Vine during pre-decline meetings in the autumn of 2015 (Lorenz, 2016).

The advent of TikTok, however, has done little to quell the romantic reminiscence on the Vine days. RIP Vine compilations still boast robust views of YouTube, while it is increasingly common to see videos with titles such as “Tik Toks that give off Vine energy”. In reflection, it is worth asking if Vine would be subject to the same posthumous canonization it if it had experienced an organic demise, as it was on track to do, rather than an abrupt corporate termination? We may never know. However, it is certain that “Do it for the Tik Tok” does not have the same ring that “Do it for the vine” once did.

References

Blistein, J. (2013, April 2). Prince Serves Twitter’s Vine App With Copyright Complaint. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/prince-serves-twitters-vine-app-with-copyright-complaint-183938/

Dijck, J. van. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

Gillespie, T. (2017). Governance of and by platforms. In J. Burgess, T. Poell, & A. Marwick (Eds.), SAGSE Handbook of Social Media. SAGE Publications.

Lorenz, T. (2016, October 29). Inside the secret meeting that changed the fate of Vine forever. Mic. https://www.mic.com/articles/157977/inside-the-secret-meeting-that-changed-the-fate-of-vine-forever

Roberts, J. (2013, May 25). Vine, hip-hop and the future of video sharing: Old rap songs and new copyright rules. https://gigaom.com/2013/05/25/vine-hip-hop-and-the-future-of-video-sharing/

0 comments on “Vine: A Critical Social Media Profile”