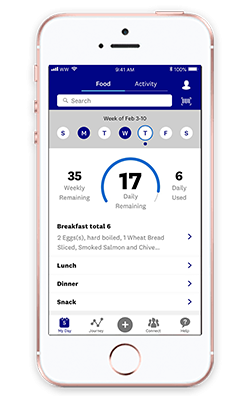

Weight Watchers is a subscription based wellness program that was founded in 1963. It developed from weekly support meetings in founder Jean Nidetch’s NYC apartment into WW International, operating in 30 different countries through its app, meetings and personal coaching (ReviewChatter, 2019). The change of Weight Watchers International to WW International occurred in 2018 due to the increasingly negative discourse surrounding diet culture at the time. They claimed to be changing their focus from weight loss to overall wellness and health. The platform as of 2020 offers users the ability to track and control their fitness and diet using daily allotted SmartPoints. Within the app users are able to search different meals and food items to find and record the associated SmartPoints, there is an in app feature that provides users the ability to scan the bar codes of items in order to learn the number of points they contain. Fitness activities can be tracked within the app, users can record their weight and health milestones and there are over five thousand low point recipes available to subscribers. Users have 24/7 access to online communication with a coach. WW International states that they help users tailor weight loss to their individual lives, eat smarter and reach personal goals. In 2019 WWI incorporated meditation programs and fitness apps in their platform in order to shift the focus away from dieting (ReviewChatter, 2019). The social media aspect of the app that provides users the chance to connect by “[sharing their] journey through photo and video and find[ing] inspiration from other members” (How to Use WW, 2020:10).

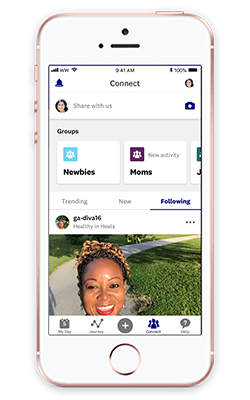

Their Connect option is described as “an exclusive members-only community” (How to Use Connect, 2019:1). There are 26,000 posts a day on the platform and it is used to share stories and pictures of wellness experiences, inspirations and successes. The hashtag feature is available to tag challenges and themes and view what is trending among users, posts can be liked and commented on by other users and there are specific groups/communities for various interests and stages in the weight loss journey such as specific sports, meal ideas and mindfulness. It is marketed as a social way to be inspired and motivated to reach fitness and health goals in a supportive, healthy and positive environment (How to Use Connect, 2019).

WW International is one of many companies that offer meal and fitness tracking in an accessible application. Their approach stands out because of the emphasis that is put on wellness and moderation instead of strict dieting and calorie counting. The SmartPoint system rates certain fruits, vegetables and lean proteins as zero points and there are extra points throughout the week that allow users to occasionally “treat” themselves. The social network aspect attempts to foster support as motivation as opposed to competition. However, as much as WW International has attempted to pull away from the idea that they are a diet and weight loss program, that is exactly what the platform is used for. The social aspect creates a space for community members to encourage and support each other’s weight loss attempts. This in turn, like any imposed diet, has the ability to encourage unhealthy relationships with food and self. The amount of points being used is privileged over actual food consumption and as a result “the program teaches members to rely on external means (points) rather than internal cues. It teaches us not to trust ourselves” Spears, 2017:20).

Users are pushed to share their healthy activities and habits publicly and by proxy feel obligated to monitor their diets and activities. The whole concept of health and wellness apps like WWI relies on the presupposition that weight loss is something that users should be constantly striving towards and frames focusing on monitoring and restricting food intake as positive and necessary to live a healthy and happy life. This is not to say that weight loss apps like WWI have not had a positive impact on many users’ lives. It has been successful at helping those who struggle with their health and given a positive non-medical community to people with weight loss goals. The problem is that the community support and motivation for weight loss that is enabled through the app can easily worsen a user’s already unhealthy relationship with food or can create one (Spears, 2017). It encourages users to “determine their success based on the number on the scale” (p.9) by celebrating weight loss and self-monitoring.

Social media platforms often reflect and foster societal norms. They are human networks and both reflect and influence the users’ values and the way they think (Dijck, 2017). The social reality that WW International reflects is the importance that society places on weight and weight loss, which WW reinforces on the platform. Social networks are often built around “dominant cultural norms and assumptions” (Lupton, 2019:129) and the self-identity and embodiment that is encouraged on WW is one that is heavily focused on diet, weight management and self-monitoring. Content that is being shared and connections made on the Connect feature revolve around further encouraging and normalizing the existing obsession with weight loss and body image.

An easily overlooked aspect of WW International and fitness apps in general is data collection. The information that is plugged into this platform is done so under the guise of self-monitoring and self-improvement. However, surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2015) plays a large role in the daily interactions with the platform. Users log everything they eat and drink. Various food items or meals from chains like Starbucks or Mcdonalds exist in the SmartPoints system and the consumption of these items are logged by users and then extractable by the platform. Daily fitness activities and weight ins are logged as well which leads to a large accumulation of valuable data about consumers. The users are valuable data sources as is the case with all social media platforms (Zuboff, 2015). Data is accumulated within the app with permission from the user through the Terms and Conditions of use listed on their website and the app itself (Terms and Conditions of Use, 2019). The user consents to WWI owning the rights to any Submissions on their app, meaning any posts, emails, and all content in general. They reserve the right “to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, communicate to the public, perform and display any Submissions” (p.12). In their privacy policy they differentiate identifiable personal information from non identifiable personal information and emphasize that the non identifiable is completely anonymous. This data includes “such as demographic information (like age, profession or gender) and physical information (like current weight) (“Non-Personally Identifiable Information”). Non-Personally Identifiable Information may also include user IP addresses, browser types, domain names, and other anonymous statistical data involving the use of our Website” (Privacy Policy, 2010:8). They use cookies and web beacons. It explicitly states in the Privacy Policy that non-personally identifiable information is disclosed to affiliates, third parties, outside contractors and advertising partners. Data and technology researcher Nick Selby (2017) says that installing the app and registering to WW users give WWI permission to access almost every aspect of the device that the app is run from. It is kept running even when not in use and has access to call logs, website searches and even network connections. This amount of access to data is now expected for free social networks such as Twitter or Facebook, however, WW users pay up to $24.99 a month to use the service along with paying with relinquishing privacy and giving full access to their non-identifiable personal information. This is an instance of platform capitalism and where there is a blurring between what separates users and producers (Dijck, 2018). The users of WWI produce content in the form of photos and text posts as well as the interaction with those posts. Their engagement with the platform by logging their diet and lifestyle for both themselves and others is a constant source of data for the company. This exemplifies Nick Srnicek’s (2017) concept of platform capitalism and the notion of ownership over information and the appropriation of data as a raw material which WWI participates in.

With WWI’s well packaged offering of their health and wellness app the company has managed to discreetly amass incredible amounts of valuable data and content through users. The social platform they offer provides users with a supportive outlet to self-monitor and obsess over the quantities of food they put into their bodies. This glorification of diet culture and weight is framed in a way that can be perceived as wholly healthy and beneficial which then allows the company to commodify their users’ lives and insecurities in various ways.

Works Cited

Canada, W. W. (2019, July 31). How to Use Connect. Retrieved from https://www.weightwatchers.com/ca/en/article/how-use-connect

Dijck, J. van, Poell, T., & Waal, M. de. (2018). Platform Society as a Contested Concept. In The Platform Society (pp. 7–30). New York: Oxford University Press.

Editor. (2019, March 11). WW (Weight Watchers) Statistics, Facts & History. Retrieved from https://www.reviewchatter.com/statistics-facts-history/weight-watchers

How Does WW (Weight Watchers) Work? (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.weightwatchers.com/ca/en/how-ww-works

Lupton , D. (2019). The thing‑power of the human‑app health assemblage: thinking with vital materialism. Social Theory & Health, 17, 125–139. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-019-00096-y

Privacy Policy. (2010, July 8). Retrieved from https://www.weightwatchers.com/ca/en/privacy-policy#1

Selby , N. (2017, April 30). The Insatiable Data Gluttony That Is The Weight Watchers Mobile App. Retrieved from http://nselby.github.io/The-Insatiable-Data-Gluttony-Of-Weight-Watchers/

Spears, K. (2017, June 13). How Weight Watchers Fueled My Eating Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.recoverywarriors.com/how-weight-watchers-fueled-eating-disorder/

Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform Capitalism. Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA: Polity.

Terms and Conditions of Use. (2019, May 30). Retrieved from https://www.weightwatchers.com/ca/en/termsandconditions-of-use

0 comments on “WW International: The Commodification of Self-Monitoring”